As Charlie Shepherd Sr. approaches his eleventh and final season as the head coach of the Salmon River football program, he doesn’t sound like a man who has guided the Savages to five state titles over a decade, much less coached a first-round NFL draft pick.

“I wish — because I still haven’t figured this out — I wish that I was better at motivating kids to be the best they can be,” Shepherd said from his home in Riggins. “I wish someone could’ve given me a magic potion where I could get the best out of every player no matter what. That sure would’ve helped me a lot.”

Then again, if you know Charlie Shepherd, that sounds exactly like him. His competitive drive and passion for coaching has propelled him to heights he never even imagined possible, especially considering that his entrance into the profession began while operating a saw at his family’s mill—the same saw that nearly took his life in January.

DRIVE TO SUCCEED

Growing up in Garden Valley, Shepherd didn’t have to go far to find competition. With nine siblings—six boys and three girls—the Shepherd household was an environment rich with rivalries.

“When you come from a family of that size, you’re poor so you have to come up with other ways to entertain yourself,” said Salmon River athletic director Paula Tucker, who is also Shepherd’s older sister.

Family competitions were a way of life.

“We played football out in the yard and we wrestled—and everything was competitive,” said Tucker, who wasn’t shy about mentioning her undefeated coaching record against Charlie while she was leading the boys basketball program at Garden Valley.

“And it’s still like that today in my brothers’ businesses,” she said. “That competitiveness was just instilled into the whole family.”

But Shepherd’s drive extended beyond the normal thirst to win—he wanted to be the best.

One season while playing high school football, Shepherd didn’t feel like he was getting pushed hard enough by the coaching staff. So, once practice ended each day, Shepherd would stay out on the field and run wind sprints on his own.

“Pretty soon, other kids on the team took note of what Charlie was doing and decided to join him,” Tucker said.

When Shepherd’s family moved to Riggins his senior year, he excelled at Salmon River, emerging as one of the top players from the Long Pin Conference. Emboldened by his success, Shepherd walked on at Boise State in the fall of 1986. He soon discovered he wasn’t built for college football, but not until he was thoroughly satisfied that was the truth.

Shepherd recalled Boise State coach Lyle Setencich having some harsh words for him and several other Idaho players hailing from 8-man football programs.

“He told us, ‘This is not small town Idaho. This is real football,’” Shepherd said. “And he made it clear right there that he wasn’t interested in having us playing for him. But I was cocky and didn’t want to give up. Eventually, I saw the writing on the wall. At 5-foot-6 and 135 pounds—and a slow 135 pounds at that—I figured out that I needed to do something else. However, I learned a lot about the game during my time there.”

Charlie and son Jimmy celebrate after the Savages defeated Ambrose 63-59 in the 2014 1AD2 State Championship.

Charlie and son Jimmy celebrate after the Savages defeated Ambrose 63-59 in the 2014 1AD2 State Championship.

AN OPPORTUNITY ARISES

In 2003, Salmon River was in desperate need of a basketball coach, so desperate that then-athletic director Linda Mann resorted to pounding the pavement to recruit someone. Her stop at the Shepherd family sawmill turned out to be fateful one.

“After we lost our coach, I had heard about Charlie and that he had just moved back into our community,” Mann recalled. “I was told that he was a really good player and very much into sports. So, with that in mind, I asked him to take the job—it was more like I begged him to take it.”

Shepherd, who was working on his family mill’s 60-inch circular saw when Mann walked up, thought Mann’s request was out of left field.

“I was a little bit of a smart ass and responded by asking her if she wanted me to coach football, too,” Shepherd said. “She then asked me if I coached football as well. I told her I didn’t coach anything and I didn’t understand why she was asking me to coach.”

Shepherd’s bewilderment wasn’t unfounded. Living permanently in Middleton and working for stretches at a time in Riggins, he didn’t have much of a coaching resume.

“When I was about 19 or 20 years old, I had coached a women’s recreation softball team in Garden Valley where the youngest player was probably 15 years older than me,” he said. “And when my oldest boys were young, I coached them in an indoor soccer league. But that was it.”

Intrigued by the prospect of coaching, Shepherd interviewed with the school and shortly accepted the job before moving permanently to Riggins.

“I got excited about it but never thought to ask her what the team was like.”

Shepherd soon learned that he’d inherited the doormat of the Long Pin, a league that had never won a boys state championship in the sport.

“We were dreadful and only won one game that first season, but mostly because we just sat around at practice talking about football,” Shepherd said.

With almost all his players also members of the football team, word eventually got back to some of the administration that Shepherd was being critical of the football coaching.

“When I sat down and spoke with (Coach Shepherd), I found out he wasn’t being critical as he was suggesting some different strategies,” Mann said.

That conversation led to Shepherd joining the football staff as an unpaid assistant for the next two seasons, serving as the team’s defensive coordinator.

“I don’t think our head coach (Brad Neuendorf) at the time liked the idea of being forced to take me on as an assistant, but things got better after our defense started playing so well,” Shepherd said.

In 2004, the Savages went 7-2 before winning the Long Pin title the next season. Then in 2007, Salmon River won the state crown. Neuendorf accepted a job in Wendell at the end of the school year.

Shortly thereafter, Shepherd didn’t hesitate to assume the head job for the football program.

“I think it was apparent to everyone that football was where my real passion was,” he said.

But Shepherd wasn’t about to quit on the basketball team either—and eventually he figured out how to win there, too.

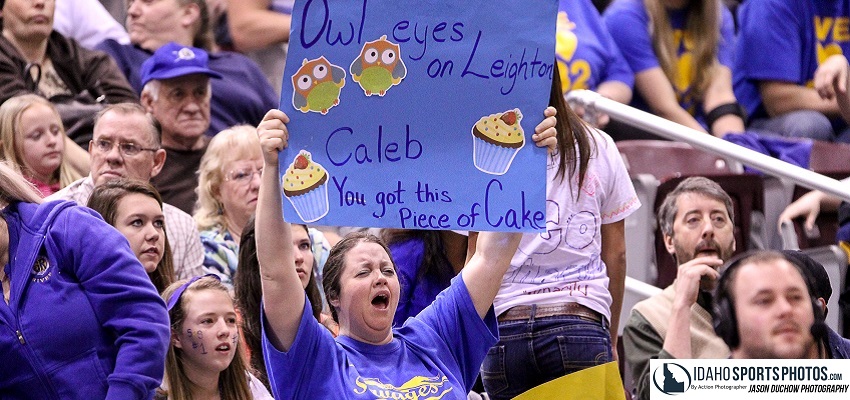

Salmon River fans cheer on their team during a basketball state championship game.

Salmon River fans cheer on their team during a basketball state championship game.

THE THREE AMIGOS

The mere mention of the name Leighton Vander Esch sparks an added excitement in Shepherd’s voice. The 2018 first-round draft pick by the Dallas Cowboys resulted in a handful of national reporters descending upon Riggins to find out how a first-round draft pick could emerge from a small tight-knit community nestled along the banks of the Salmon River and the Little Salmon River. Shepherd was more than happy to sing the praises of his star player.

But Shepherd’s ties to the Boise State standout and now-Dallas star hopeful go back to a childhood friendship between Shepherd’s two oldest sons and Vander Esch.

“Charlie (Jr.) and Jimmy were all tight,” Shepherd explained, with Vander Esch being sandwiched in age between Shepherd’s two eldest sons. “They were best friends growing up, and they started first making magic together in little league baseball.”

As Vander Esch’s coach for football, basketball, and track, Shepherd could easily take credit for Vander Esch’s success. But he’s quick to deflect away from that.

“Darwin and Sandy, Leighton’s parents, did a lot of the hard work for me,” Shepherd said. “Their family was a lot like ours in the fact that not only was there an emphasis on being a good ballplayer but also on being the best you could be at whatever you were doing. Leighton really took that to heart and the results speak for themselves.”

By the time Vander Esch, Charlie Jr. and Jimmy had all reached high school in 2012, Shepherd had already led the Savages to a state title in 2009—but he sensed there was an opportunity to win more. The Savages’ 2011 season ended in a humiliating 46-0 loss at home to Lighthouse Christian, setting the stage for the trio’s breakout party.

In 2012, Salmon River had a chance to avenge its loss to Lighthouse Christian in the 1AD2 state championship game played at Eagle High School. Vander Esch and the Shepherd boys put on a show en route to a 54-38 victory.

“Between Leighton extending the plays and Charlie (Jr.) and Jimmy making great catches—that was the most fun I ever had coaching that night,” Shepherd said. “On both sides of the ball, those kids just made play after play. And that was a game we were supposed to lose handily. That was also the night that everyone saw just how special of a player Leighton was.”

It was also the game that sent then-Boise State linebackers coach Andy Avalos to Riggins to investigate if Vander Esch’s exploits were truly legendary or embellished myth. Avalos, who eventually offered Vander Esch a scholarship, and the rest of the nation learned last season in Vander Esch’s first—and only—season as a starter that it was the former.

Shepherd is also quick to point out that he’s been fortunate to have so much talent in such a small community.

“I’ve had a few other kids go on to do special things and play in college,” Shepherd said. “Charlie was a four-year player at the College of Idaho and Jimmy played at Lewis-Clark Valley. And Dustin Rinker went to Carroll College and became the school’s career rushing leader. And there were others too. And they’re all a big reason why we’ve had so much of the success we’ve had. They certainly have all made me look better as a coach.”

Shepherd, who was still leading the basketball program at the time, enjoyed coaching Vander Esch and his sons to back-to-back football and basketball titles during the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years.

“The only reason we didn’t have success in baseball was because we didn’t have enough players to field a team,” Shepherd quipped.

The titles on the hard court were the first ever for a Long Pin district school.

And while he reaped the benefits of a talented group led by a future first-round NFL draft pick, Shepherd set out to prove that he could win without such elite talent. After missing the playoffs all together, he led Salmon River to back-to-back football titles in 2015 and 2016.

Vander Esch runs the ball during 2013 1AD2 Football State Championship against Council. Salmon River would win 66-22.

A SCRAPE WITH DEATH

That same circular saw Shepherd was working on when his coaching career sprang to life was the same place he nearly died earlier this year.

On January 4, Shepherd was sharpening the sawmill’s 60-inch blade by hand, a tool he’s worked on for the past 20 years. In a hurry to get things finished around the shop, he neglected to turn off the main power source, while the rest of the crew was doing general maintenance work. When someone turned on the power, Shepherd was straddling the blade.

“By all rights, it should’ve cut me in half,” Shepherd said. “But instead, it grabbed my leg and then threw me across the room.”

The blade sliced a 24-inch cut from the back of his knee to his rear end but miraculously missed all major arteries. Between the initial surgeries and skin grafts, Shepherd spent nearly three weeks in and out of the hospital.

Just two days before the NFL draft in April when he was supposed to travel to Dallas for Vander Esch’s big moment, doctors released Shepherd, clearing him to go.

“When you go through something like that, it certainly changes your perspective on life,” Shepherd said.

Now he’s running around on the football field again like the near-death experience never even happened physically—but the incident certainly made an impact on him.

The saw at the Shepherd Sawmill that nearly ended Charlie Shepherd's life.

The saw at the Shepherd Sawmill that nearly ended Charlie Shepherd's life.

A NEW SEASON

With a fresh look on life and the last of his four children, Chevelle—a state champion pole vaulter—graduating from Salmon River next spring, Shepherd has stated that this season will be his last at the helm of the Savages’ football program. But it’s a decision that he hasn’t made hastily—and it’s one that he doesn’t sound completely sure about.

“Getting to coach my kids has been an absolute delight, and I’d feel guilty if I didn’t give that chance to someone else,” Shepherd said. “I was able to coach Charlie (Jr.) to four state championships and my other two sons, Jimmy and Johnny, to two—and that made it even more special.”

The Shepherd family after a College of Idaho football game, Left to Right: Johnny, Jimmy, Susan, Charlie Jr., Charlie Sr. and Chevelle.

The Shepherd family after a College of Idaho football game, Left to Right: Johnny, Jimmy, Susan, Charlie Jr., Charlie Sr. and Chevelle.

Shepherd already went down that path in basketball, yielding the program to his nephew, Levi Tucker, so he could coach his son.

“The timing just worked out for the transition,” Levi said. “I was already coaching the JV team and had a chance to be around him and see how he ran things. He definitely left me some big shoes to fill.”

Though nothing has been finalized, Shepherd’s top assistant Ty Medley appears primed to take over the football program. Shepherd sees a lot of himself in his young protégé, who was a member of Shepherd’s first coaching class.

“Ty’s just like I was when I first got on the job,” Shepherd said. “He’s real gung-ho and ambitious. And he’s getting better in learning how to motivate the kids. If there wasn’t someone capable of taking over the program, I’m not sure I would want to hand it over.”

Even as the season is barely a couple of weeks old, Shepherd sounded nostalgic as he mentioned what he’s likely to miss the most.

“I’ll miss the kids,” Shepherd said. “I really enjoying going out there every night and practicing with the kids and really teaching them the game of football.”

It’s Shepherd’s unorthodox approach to coaching that has enabled him to focus on other details. Without a playbook, Shepherd entrusts his players to get a feel for what plays they should run.

“A lot of coaches shove a playbook into the kids’ hands and expect them to memorize everything,” Shepherd said. “I want them to learn plays and I teach them how to put together a drive. But more than anything I want them to understand the game. I want them to know why they need to make a certain block and how they can recover to make a great play. In 8-man football, if you make a mistake, everyone feels it so much more. You have to learn how to play as a team before you learn a series of plays.”

Whether it’s at the end of a season-ending loss or a sixth state title, when Shepherd walks off the field at the end of the season, there will be a void in Riggins.

“I had no idea it was going to work out the way it did,” Mann said of hiring Shepherd. “But Charlie has been a great asset to our community ever since.”

“It’s going to be hard,” Shepherd said of coaching his final game for Salmon River. “The timing feels right and I know I’ll want to have more time next year to go watch my daughter compete next year in college, but I’m definitely going to miss coaching football, especially when that first Friday night rolls around and I’m not on the sideline.”

When Shepherd walks off the field at the end of the season, he won’t have a magic potion to pass along to the next coach, but he will definitely have a winning formula.